Rethinking Asian American Identity in the Post-DEI Era

Has the window closed on Asian American storytelling?

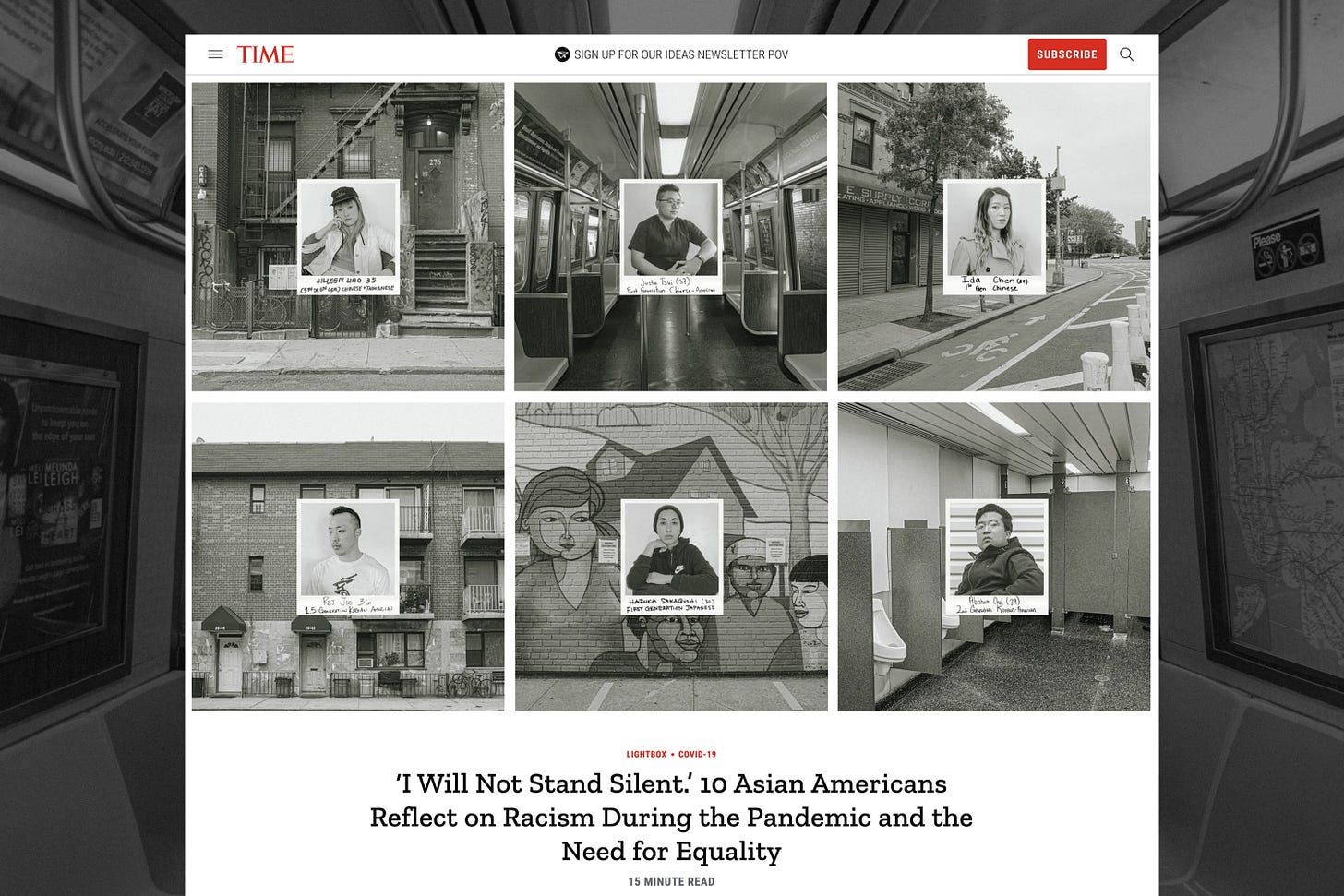

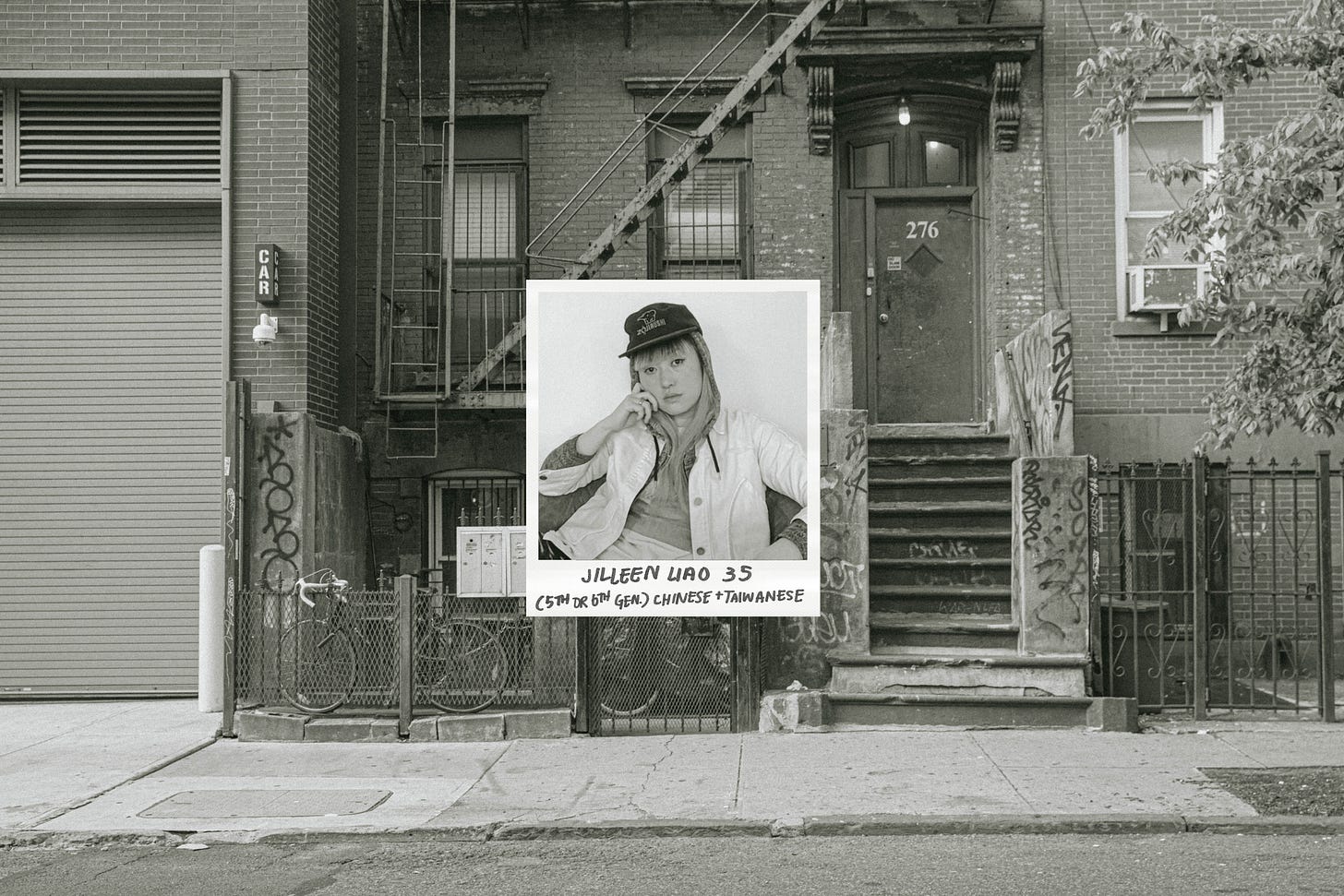

Next month marks five years since I Will Not Stand Silent—a story I photographed for TIME Magazine—was published during the height of the pandemic on July 6, 2020.

Here’s the premise: In the wake of COVID-19 lockdowns and Trump’s “kung flu” rhetoric, anti-Asian attacks surged. We profiled ten Asian Americans in New York City who experienced verbal and physical harassment at the onset of the pandemic, exploring how their perspectives shifted amid the broader racial reckoning triggered by the Black Lives Matter protests.

The story struck a chord. It received a Newswomen’s Club of New York Award and the Duke Archive of Documentary Arts Collection Award. It was a finalist in Pictures of the Year International. It was exhibited at Photoville and later displayed in the halls of Columbia Journalism School.

The piece came out during a rare moment of heightened interest in Asian American narratives. From Shang-Chi to Everything Everywhere All at Once, Asian diasporic stories were surfacing in the mainstream discourse. Initiatives like Stop AAPI Hate and legislative efforts such as the TEAACH Act signaled tangible shifts toward inclusion and visibility.

Cut to: five years later.

The media attention has waned. Race and identity desks at major media outlets have scaled back their coverage. Asian American artists and writers who sold in the 2020 boom are struggling to land new contracts. Public conversations around Asian American identity have become deeply fragmented.

Even the term “Asian American” itself has come under scrutiny. Cathy Park Hong has called it a "tenuous alliance" of diverse nationalities. Jay Caspian Kang has argued that the term is "mostly meaningless," a catch-all phrase that flattens class distinctions and cultural nuances into a marketable identity.

It’s a fair point: grouping over 20 million people from dozens of countries under a single umbrella inevitably breeds conflict. As an East Asian immigrant, I will never fully understand the lived experiences of a newly arrived refugee from Southeast Asia or a U.S.-born activist like Grace Lee Boggs.

The unraveling continues. We now live in what some call the “post-DEI era.” The same president who once fanned anti-Asian hate during the pandemic is back in office. Within days of his inauguration, federal DEI programs were dismantled. Major corporations followed suit, quietly pulling back funding, fellowships, and initiatives that had briefly carved out space for our stories.

For many marginalized communities, this cycle feels painfully familiar:

Tragedy, followed by

Outrage, followed by

Performative allyship, followed by

Fatigue, and ultimately–

Silence.

So where does that leave us?

Has the window closed on Asian American storytelling?

Contrary to popular understanding, the term “Asian American” was never intended to be a cultural identity—it began as a political coalition. Coined in 1968 by student activists Emma Gee and Yuji Ichioka during the formation of the Asian American Political Alliance, it was an explicitly political movement that called on Asians of all backgrounds to fight against U.S. imperialism abroad and racial injustice at home, in solidarity with Black, Latinx, and Indigenous movements.

The original vision for “Asian America” was never centered on a shared identity, but rather, a shared commitment to advance justice for all marginalized groups. It was conceived by activists who refused to let their liminal status as “perpetual foreigners” sideline them—instead, they used it to build alliances across movements.

It was only later, with post-1965 waves of immigration—myself included—that this coalition was reduced to the meek and sanitized cultural identity that we know of today, defined by tired clichés like boba, anime, and the desperate pursuit of white proximity. Which is why—understandably—some Asian Americans are hesitant to embrace the term. It no longer feels like the galvanizing force it once was, and more like an imposition.

Working on this story was cathartic for me because it offered a glimpse into the true origins of Asian America. I was reminded that being Asian American doesn’t have to be a fixed identity defined by a single-track trajectory toward assimilation or the life-long struggle of reconciling heritage with survival—that I can be more than just someone desperately trying to fit in.

Rather, being Asian American boils down to a political choice: to pursue acceptance within an exploitative system, or to use one’s liminality to advance justice for all Americans.

Today, the appetite for Asian America as a cultural commodity is waning. But instead of mourning the loss of this media attention, what if we rejected this tepid, marketable identity altogether and returned to our roots as a political coalition for justice?

Since the pandemic, cross-racial solidarity movements between Asian Americans and other groups have reemerged—from South Asian coalitions organizing in solidarity with Black Lives Matter, to Asian American organizers standing with Palestinian activists opposing the Gaza occupation, to Japanese American organizations supporting HR 40 and demanding the closure of ICE detention centers.

Asian Americans are descendants of a stunningly imaginative and forward-thinking coalition: one that didn’t require drinking out of the same well of hardship to build alliances, one that looked beyond archaic notions of purity or “sameness” to envision a more interconnected world. We were united not by a shared identity or struggle, but a shared vision for equality and justice.

In this “post-DEI era,” Asian Americans are confronted with a choice, once again: do we lament the closing window, the fleeting media attention, the rollback of the representation that we had worked so hard for? Or do we use our liminality as a bridge toward deeper solidarity and collective action?

It may be time to choose the latter.

Endless thanks to my photo editor Sangsuk Sylvia Kang. Her trust, reporting and discerning eye made this project possible.

View the full edit here.

Read the article here.

Fangirling ✨

Lisa Elmaleh’s project, Tierra Prometida, is a breathtaking project chronicling the stories of asylum seekers attempting to cross the U.S.-Mexico border. Her work was recently featured on High Country News.

U.S. Deported Bhutanese Who Were Here Legally. They Are Now Stateless. photographed by Hannah Yoon and edited by Stephen Reiss. Sensitive and poignant coverage of a refugee community gripped by confusion.

To Visit My Home, I Visit Its Borders photographed by Sara Kontar and edited by Eslah Attar for The New York Times Opinion. A poignant and sensory account of longing from the Syria-Jordan border.

You’re receiving this email because you subscribed to my newsletter or we’ve worked together in the past. If it's not quite your thing, you can unsubscribe anytime using the link below.

Haruka, I didn't know you were such a talented writer in edition to being a talented photographer. I posed this question last night a durian club meetup - is there enough there to bind us together under the Asian American moniker? I think there is but what I'd argue is politically we are not bound. There are two movements happening among Asian Americans - one movement focuses on visibility and is racing to be white adjacent, and the other is focused on cross-racial solidarity and elevating everyone. Jay posits in Loneliest American: are you going to side with the oppressor or the oppressed? I know which side I'm on and I think the disconnect is that others have not quite made up their minds. I wrote this piece once Asian American Heritage month wrapped and it went viral on LinkedIn. It touched a nerve because I think people felt the divergence but couldn't quite name it: https://wnguyen.substack.com/p/the-crazy-rich-asians-movement