When I first decided to pursue photography in 2016, I had a day job as a graphic designer. From Monday to Friday, I worked in an office in Manhattan. On weekends, I convinced friends and friends-of-friends to meet me in random locations—parks, rooftops, Brighton Beach at the a** crack of dawn—so I could photograph them. I’d come home, feverishly edit the photos for the rest of the weekend, and then start the cycle all over again the following week.

From 2013 to 2016, I quietly built my portfolio. What began as an awkward compilation of grainy, high-contrast portraits gradually became something more coherent. I told myself that one day, I’d book enough commissions to leave my design job. That one day, I wouldn’t have to cram back-to-back photoshoots on Saturdays and Sundays. That one day, I would become a full-time photographer—not a designer with a DSLR camera.

I received my first commission for a major publication in 2017. Gradually, assignments started to trickle in. I photographed everything from lighthearted reads on how Deepak Chopra spends his Sundays to investigative pieces on activists under government surveillance. I was over the moon—this dream that had once felt indulgent and unattainable was finally starting to take shape. I eventually left my full-time position and became an independent contractor with the same company, hoping to free up time for photo assignments.

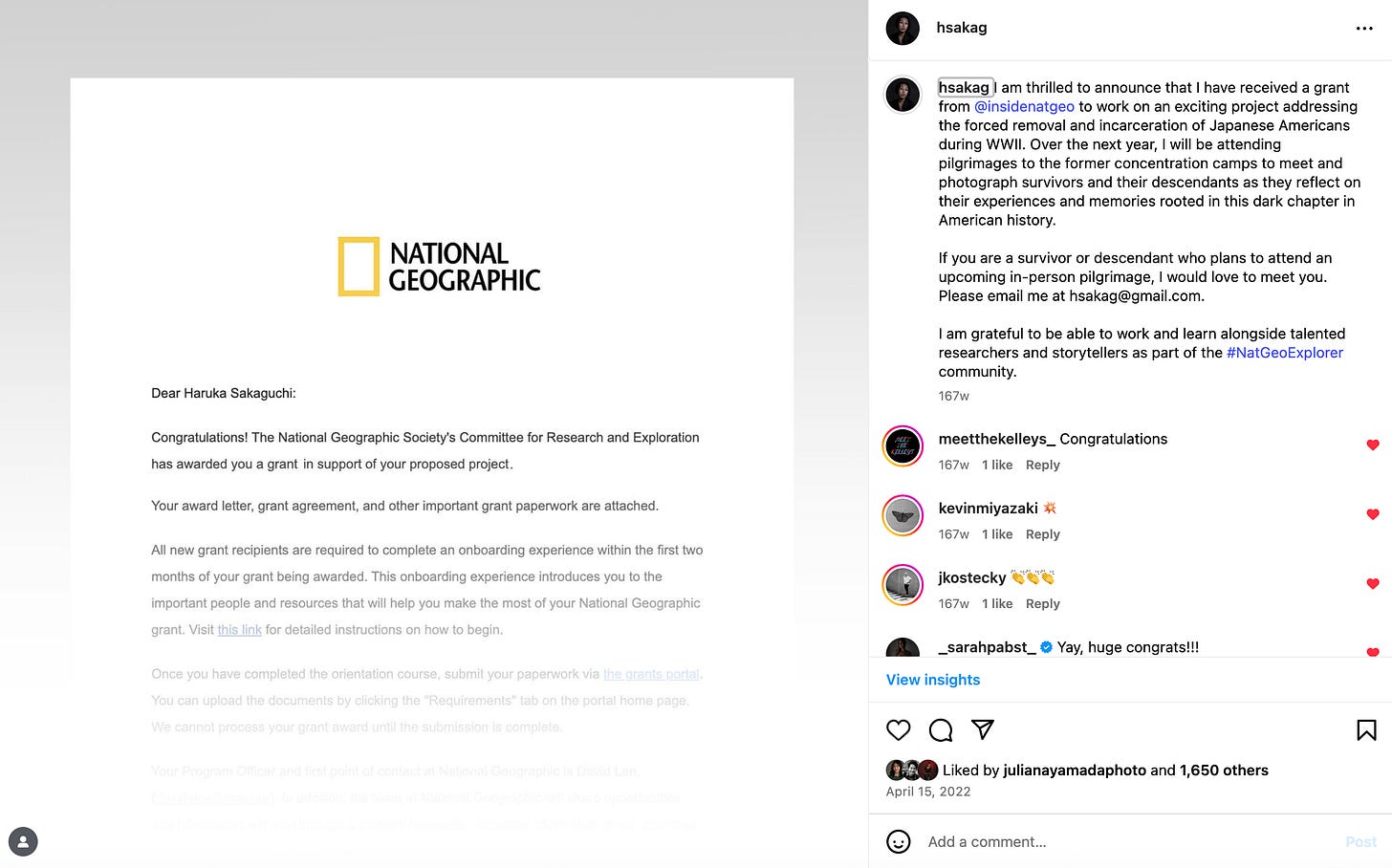

In 2020, a project I pitched ran in TIME Magazine. In 2022, I received a grant from the National Geographic Society. From the outside, I was checking all of the boxes—bylines, grants, awards. But here’s what no one saw:

I never stopped taking on design work.

I used to think this made me a fraud: that clinging to a secondary source of income was proof that I wasn’t talented enough or committed enough to my photographic practice. I pictured “real” photographers as steely and mission-oriented, lugging camera gear across the country and risking their lives to get the perfect shot.

Meanwhile, I spent half of my week at home in an air-conditioned apartment pushing pixels on InDesign. My inner voice wanted to devote all of my waking hours to projects I believed in—but my hyperactive nervous system and immigrant upbringing kept me tethered to a more stable income.

As I settle into my mid-30s, however, my perspective has shifted. I no longer see my patchwork career as a weakness or liability. I see it as protection against burnout, industry volatility, and the often romanticized trope of the “starving artist.”

Today, editorial day rates average around $450 per day, before taxes. To earn a living wage as a freelance photographer in New York City—where a single adult needs at least $49,986 after taxes to cover basic expenses, according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator—you’d need to be on assignment at least 15 days a month.

For those outside the industry: consistently landing that many assignments every month—especially in today’s saturated media landscape—is no easy feat. Editorial commissions are highly competitive, unpredictable, and often slow to green-light. In this climate, relying solely on editorial assignments isn’t just stressful—it’s virtually impossible.

There’s no shortage of articles urging freelance photographers to pile on tangentially relevant side projects like selling Lightroom presets or launching an online course. Personally, I find this brand of advice hit-or-miss—after all, not all of us are wired to peddle products or become camera-slinging influencers.

In this subscribers-only Studio Hours post, I share three strategies that have helped me make the most out of my existing practice and cultivate a more sustainable career as a freelance photographer:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Framework to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.