What I Learned Photographing Atomic Bomb Survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki

Write beside hibakusha, not about them

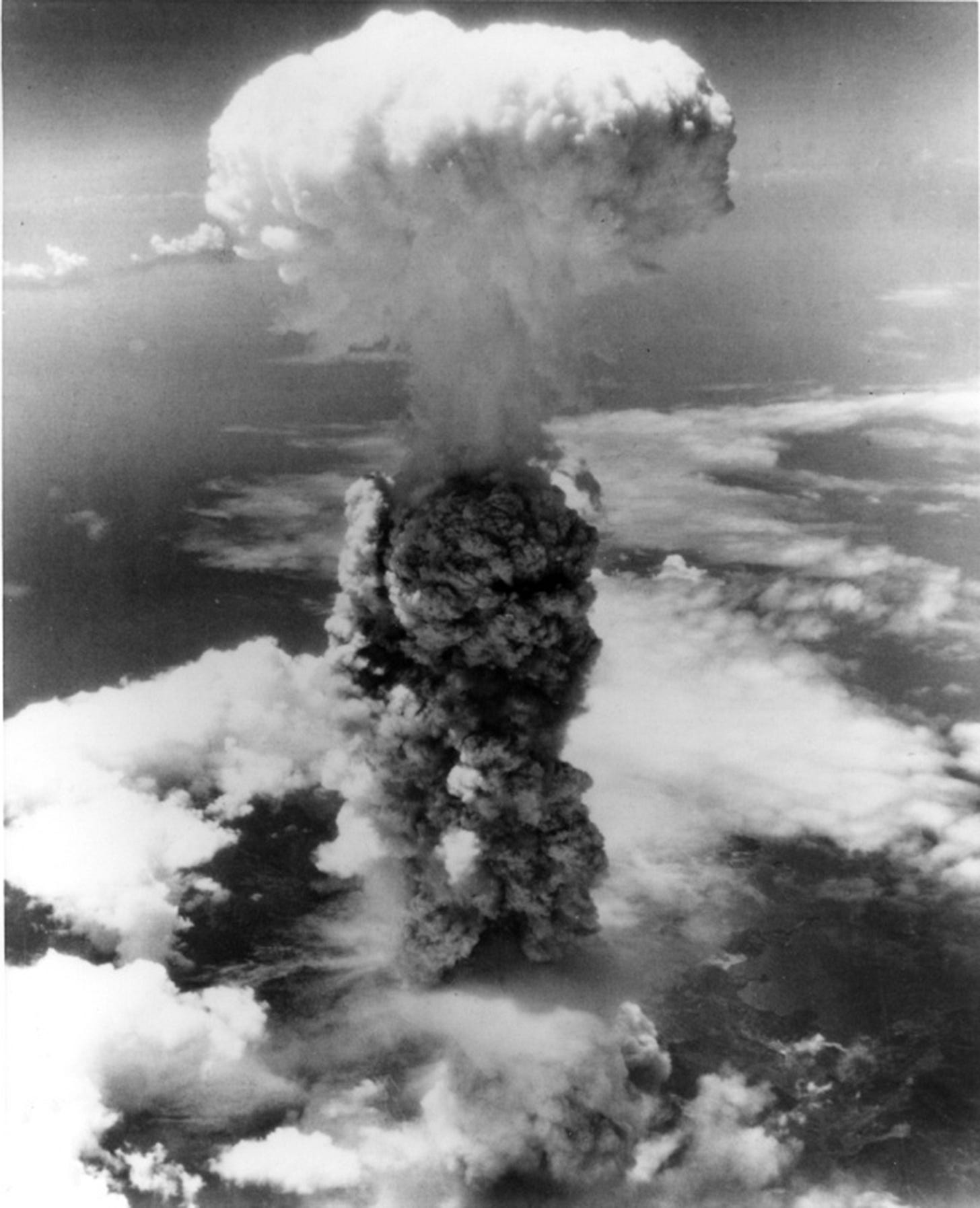

Today marks 80 years since the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, followed by a second bomb on Nagasaki three days later. In commemoration, I’m revisiting 1945, a long-term project that traces the aftermath of the bombings through portraits of hibakusha—or atomic bomb survivors—and their descendants.

Here’s the premise: On August 6 and 9, 1945, the U.S. dropped two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing between 129,000 and 226,000 people by the end of that year. Those who survived faced long-term health complications related to radiation exposure, as well as social stigma and discrimination that extended to their children and grandchildren. Through portraits, testimonies, and handwritten letters to future generations, 1945 explores the question: how did the atomic bomb shape human lives?

The project began, as many stories do, with a gut feeling. I grew up in the U.S. public education system, where a middle school history teacher once told the class:

“The atomic bombs were a necessary evil to prevent the deaths of millions more Americans and Japanese.”

As an inquisitive and perpetually skeptical teenager, I wondered: what makes a bomb “necessary”? Was the death of hundreds of thousands of people justified, simply because it may have prevented others?

This justification—compounded by the troubling suggestion that the atomic bomb was an act of benevolence that saved lives—didn’t sit right. Years later, I began to unpack it through photography.

The first hibakusha I had the privilege of meeting was Yoshiro Yamawaki. He was 11 years old when the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

He and his brothers survived the blast, but later discovered their father’s body near his workplace. They watched in horror as piles of bodies were being dumped into a mass cremation site. Mr. Yamawaki and his brothers—none of whom were older than 16 years old—found the courage to pull their father’s body out of the rubble and give their father a private cremation, the customary way of honoring the dead in Japan.

As Mr. Yamawaki calmly recounted the moment he and his brothers built a fire to cremate their father’s body, I broke down in tears.

“You idiot,” I thought. “Who cries in front of their sitter?”

Mr. Yamawaki placed a hand on my shoulder and patiently waited as I pulled myself together. By the end of that interview, I was convinced that I wasn’t cut out for this. I had stumbled through an hour-long interview and somehow managed to make a grieving man console me as he relived the most traumatic moment of his life.

That night, I mourned the early death of my project—and possibly my photojournalism career—and began packing my bags to return to the United States. But the following morning, I woke up to an email from a woman who had heard about my project. “My mother would like to speak to you,” she wrote. “She’s a hibakusha from Hiroshima.”

And so, the project continued.

During my research, I noticed that existing coverage of hibakusha often fell into one of two categories:

1. The parachute profile, or emotionally charged stories published during the A-bomb anniversaries by reporters who parachute into Hiroshima or Nagasaki for a day or two. These offer moving first-hand accounts of the bombing itself, but often lack continuity or context, especially around the ongoing realities hibakusha and their families continue to face.

2. The rallying call, or sweeping, cause-driven narratives that position hibakusha as moral symbols in the global campaign for nuclear disarmament. Important, yes—but often monolithic. These stories lean so heavily on advocacy that individuals are reduced to stand-ins for a cause.

In both cases, hibakusha were framed as either symbols of suffering or mascots of hope—rarely as multidimensional human beings. What was missing were stories that reflected the hibakusha’s inner conflict: those who resented the U.S. for dropping the bombs yet also lamented Japan’s wartime leadership; those who grieved their own suffering while grappling with guilt for passing it on to their children; those who felt called to public activism but ultimately chose a life of silence.

As I searched for ways to address this narrative gap, my mentor—second-generation hibakusha Keiko Okinishi—offered a piece of advice: write beside hibakusha, not about them. How can I tell stories beside hibakusha, rather than about them?

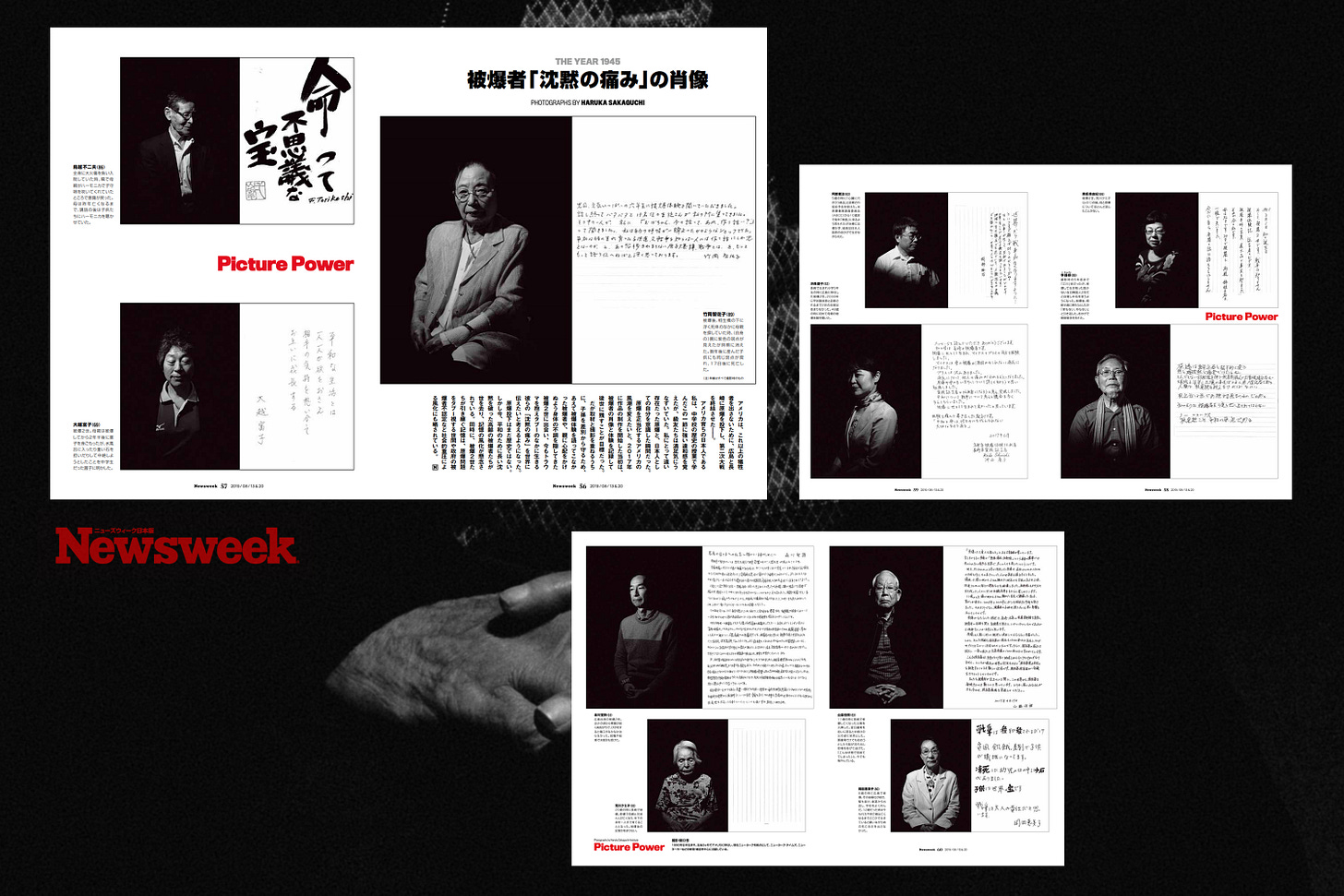

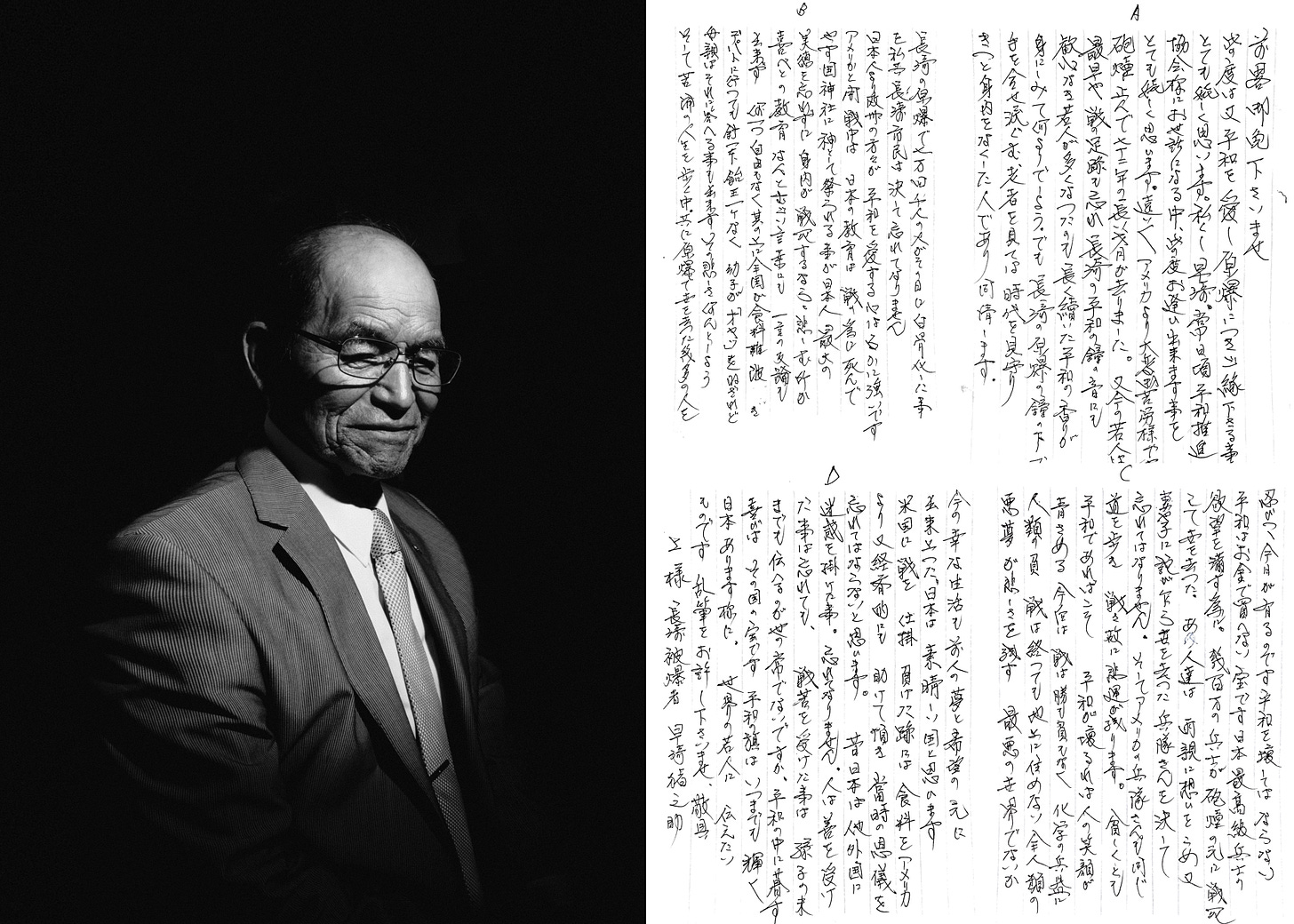

That question led to an idea: What if I invited the hibakusha to be the authors of their own portraits? Some weeks later, I landed on asking each sitter to handwrite a letter to future generations to showcase alongside their portraits.

At first, I worried this involved process would make things complicated: the risk of re-traumatization, for one, not to mention the language barrier between the hibakusha and my English-speaking audience.

But what followed was an outpouring. I asked each hibakusha for a one-page letter—some enthusiastically brought four. The letters offered something that I couldn’t: the hibakusha’s authorship.

This choice wasn’t always met with enthusiasm. Some editors passed on the project, calling the handwritten letters “too conceptual.” Others saw the language barrier as a major obstacle.

Still, I continued with the letters. If the goal was to tell stories beside hibakusha—not about them—then it meant doing things differently.

Over the next two years, I photographed and interviewed more than 50 hibakusha and their descendants. Through their letters, I learned about radiation sickness, survivor’s guilt, and the weight of remembrance. I also learned about the lesser-known struggles their children and grandchildren face—chronic illnesses, discrimination in marriage and employment, and the inherited silence that so often follows trauma.

On this 80th year anniversary of the atomic bombings, I’m thinking about the hibakusha who entrusted me with their stories. I’m thinking about their children, and their children’s children, who continue to carry the legacy of a war they didn’t choose. And I’m thinking about the narratives that deserve more space—not the parachute profiles or rallying calls—but the stories that surface when you write beside others, not about them.

View the edit here.

View the project website here.

Takeaways 📝

Follow the gut feeling. The project was inspired by a gut feeling after a history lesson. That initial discomfort—the gut feeling that something isn’t right—was what inspired this project.

There’s room for heart. When I broke down in front of my sitter during my first interview, I thought my tears were painfully inappropriate, not to mention unprofessional. But over time, my perspective has shifted. Journalistic integrity isn’t always defined by a steely disposition or disaffected neutrality. Sometimes, it looks like care.

Write beside people, not about them. This philosophy became the project’s guiding principle. What I feared would complicate the process—re-traumatization, language barriers, logistics—led to the project’s most meaningful contribution: the hibakusha’s authorship.

Fangirling ✨

Arin Yoon’s project, The Scars of War, is a breathtaking project chronicling her husband’s return from 24 years in military service. Her work, edited by Laura Oliverio and Brett Roegiers, was recently featured on CNN.

“Noah Is Still Here,” photographed by Stephanie Sinclair and edited by Jessica Dimson and David Carthas for The New York Times Magazine. In awe of their intimate coverage of a family’s unwavering care for their son, born with trisomy 18.

“How cicadas became the soundtrack of Provence — and a symbol of rest” photographed by Sasha Arutyunova and edited by Cameron Judith Peters, a selection of which appeared in a recent issue of National Geographic Magazine. A sun-soaked portrait of a 130-year-old ceramics workshop in Aubagne, France.

You’re receiving this email because you subscribed to my newsletter or we’ve worked together in the past. If it's not quite your thing, you can unsubscribe anytime using the link below.

Thank you for sharing your experience and insights. It is of course important to approach trauma and pain with sensitivity, but you also share a really important lesson here. Oftentimes, documentary work can overlook the importance of allowing those with the lived experience to actually author their own stories, rather than simply being the subject. As hard as it may have been for many of these individuals to recount their experiences, I'm sure that it was also empowering and healing. Also, your vulnerability and empathy is your STRENGTH, not your weakness. I understand the sentiment that showing emotions can be a negative thing, but it is through your emotions that you are able to tell these stories with so much grace and care. Never forget that empathy is your superpower.

Thank you for thoughtfully sharing your sensitive approach to this important and lasting legacy work. Invaluable work Haruka.